Slavery, Serfdom and Mezzadria

It

is all very well for us to wax romantic over the Tuscan countryside,

its rows of smoky olives, the lines of vines, its ancient drystone

terracing, handsome stone farmhouses and grand villas. These

elements are indeed harmonious and pleasing to the eye. But their beauty

may be incidental. Sadly,

this marriage of natural materials and the painstaking husbandry of the

land are also testimony to an ancient institution which at best

discouraged innovation and at worst was downright exploitative and extremely harsh, at least for many.

In the season when the peasant dwellers of Le Ripe, man, woman and child, would have been labouring hard in the fields to harvest the crops, it seems timely to reflect on the system which informed every aspect of their lives, from how and where they lived, how much they worked and with what tools and commitments, to their relationships with the landowner and with anyone else who was not a peasant.

Although not slavery and not serfdom (servitu' della gleba means 'servant of the clod': the relationship between landowner and serf was highly restrictive juridically and practically since the serf was literally bound to the land he worked on), mezzadria developed in central Italy in particular, after the disappearance of feudal serfdom.

Mezzadria can be translated as share-cropping and it implies 'sharing half': the institution had its roots in Roman times

but evolved and expanded during the early middle ages. Essentially, the landowner

provided the land, the house, some of the equipment and stock while the

peasant capofamiglia or head of the family provided the labour: not just his own, but that of his entire

family. Produce and eventually profits were shared in different proportions depending on certain variables.

Here is an early mezzadria contract from the 15th century which I have paraphrased below.

"A nome di Dio amen.1405 a dì 1 di Novembre. Sia manifesto a qualunque

vedrà questa iscritta, come Piero di Nello, dipintore del popolo di

Santa Maria Alberigi di Firenze, alluoga oggi, questo dì, mio podere

posto nella villa di Rabatta, comune del Borgo San Lorenzo, a Giovanni

di Nuto, chiamato Cerretta, e a Benvenuto e a Biagio figlioli del detto

Giovanni, con questi patti e condizioni:

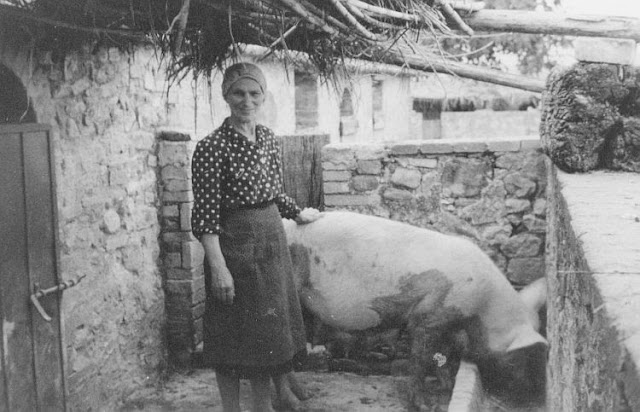

- che detto Piero deba comperare un paio di buoni buoi, sufficienti a lavorare el detto podere e debasi stare per metà di vendita e compra, e ciò che n'avvenisse; e deba il detto Piero fornire di tutti i porci e pagare ogni anno, e detti lavoratori gli debbino tenere infine al tempo competente e rendere per metà;

- e deba il detto Piero mettere mezzo seme e sovescio e concime di mezzo

- e deba il detto Piero fornire el lavoratore d'ogni bestia che volesse tenere e in quantochè il detto Piero non lo fornisse ne possa torre da chiunque e' vole,

- e deba il detto Piero fornire d'ogni strame che bisognasse il primo anno e dal primo innanzi se mancasse debbasi comperare per metà;

- e deba il detto Piero prestare a detti lavoratori fiorini 30 d'oro di suggello, cioè fare l'ampromessa per tutto il mese di giugno e anche i detti lavoratori vorrranno, cioè fare il pagamento per tutto il mese di ottobre prossimo che verrà; e detti lavoratori debbano rendere e restituire e' detti denari al detto Piero a quel tempo che eglino avessino a uscire del luogo sopraddetto;

- e' detti lavoratori debbono rimettere e mantenere le fosse sì che stiano bene ogni anno;

- e' detti lavoratori debano vangare ogni anno staiora 12 di terra a seme o più;

- e' detti lavoratori debbono porre ogni anno trenta piantoni o più di albero o di salcio;

- e' detti lavoratoridebano mettere opere quattro a ricoricare la vigna;

- e debano i detti lavoratori per Ognissanti dare al detto Piero paia due di capponi e dieci serque d'uova ogni anno;

- e' detti lavoratori debano tenere un fanciullo da bestie in quanto eglino non ne fussano forniti da loro;

- e' detti lavoratori debano rendere ogni anno la metà di tutte le frutte ed ogni caso che si ricoglie in sul podere;

- e' detti lavoratori debbono pigliare e' porci quando il detto Piero vorrà darli loro. Io frate Francesco di Francesco da Firenze, guardiano del luogo dei Frati Minori, cioè di San Francesco al Borgo a San Lorenzo in Mugello, ho fatta questa iscritta a loro priego e di loro consentimento e pertanto l'ho scritta di mia propria mano. Anno, dì e mese di sopra nominato"

- che detto Piero deba comperare un paio di buoni buoi, sufficienti a lavorare el detto podere e debasi stare per metà di vendita e compra, e ciò che n'avvenisse; e deba il detto Piero fornire di tutti i porci e pagare ogni anno, e detti lavoratori gli debbino tenere infine al tempo competente e rendere per metà;

- e deba il detto Piero mettere mezzo seme e sovescio e concime di mezzo

- e deba il detto Piero fornire el lavoratore d'ogni bestia che volesse tenere e in quantochè il detto Piero non lo fornisse ne possa torre da chiunque e' vole,

- e deba il detto Piero fornire d'ogni strame che bisognasse il primo anno e dal primo innanzi se mancasse debbasi comperare per metà;

- e deba il detto Piero prestare a detti lavoratori fiorini 30 d'oro di suggello, cioè fare l'ampromessa per tutto il mese di giugno e anche i detti lavoratori vorrranno, cioè fare il pagamento per tutto il mese di ottobre prossimo che verrà; e detti lavoratori debbano rendere e restituire e' detti denari al detto Piero a quel tempo che eglino avessino a uscire del luogo sopraddetto;

- e' detti lavoratori debbono rimettere e mantenere le fosse sì che stiano bene ogni anno;

- e' detti lavoratori debano vangare ogni anno staiora 12 di terra a seme o più;

- e' detti lavoratori debbono porre ogni anno trenta piantoni o più di albero o di salcio;

- e' detti lavoratoridebano mettere opere quattro a ricoricare la vigna;

- e debano i detti lavoratori per Ognissanti dare al detto Piero paia due di capponi e dieci serque d'uova ogni anno;

- e' detti lavoratori debano tenere un fanciullo da bestie in quanto eglino non ne fussano forniti da loro;

- e' detti lavoratori debano rendere ogni anno la metà di tutte le frutte ed ogni caso che si ricoglie in sul podere;

- e' detti lavoratori debbono pigliare e' porci quando il detto Piero vorrà darli loro. Io frate Francesco di Francesco da Firenze, guardiano del luogo dei Frati Minori, cioè di San Francesco al Borgo a San Lorenzo in Mugello, ho fatta questa iscritta a loro priego e di loro consentimento e pertanto l'ho scritta di mia propria mano. Anno, dì e mese di sopra nominato"

To

the best of my understanding (the document is ancient and quite

unclear, but I can transmit the gist of it) the contract was drawn up in

1405 between a landowner, Piero di Nello ('painter', so not a particularly wealthy landowner presumably) and

a peasant, Giovanni di Nuto and his sons Benvenuto and Biagio. For his

part, the landowner provides the farm, the farmhouse; the oxen and swine whose cost will be defrayed later

and half the seeds and fertilizer; other animals and fodder will be provided

but half will be paid for in kind when the contract expires. A loan of

gold coin as a 'seal' to the deal will also be repaid. In return the peasants must provide their labour, keep

the ditches clean, hoe the fields, plant 30 trees per year, work the

vines, provide the owner with capons and eggs, keep a shepherd boy, give

the owner half the harvest and half all produce; accept the swine the

owner gives them to tend.

The document was written and witnessed by a Franciscan friar at Borgo San Lorenzo in the Mugello.

This contract does not differ greatly from those drawn up in Tuscany in subsequent centuries until as late as the 1960s. It must be understood that such contracts did not prevent able and fortunate mezzadri from acquiring land of their own and bettering their situation over time (impossibilities for serfs).

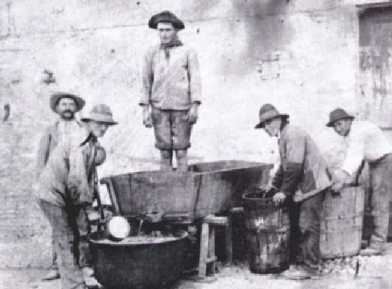

Not only did the sharecropper have to know about cultivation and animal husbandry, he had to be a craftsman, a woodsman, a shepherd and much else besides, while the women in the household were housewives, fieldworkers, foragers, bakers, weavers - and much else besides.

In the rural hierarchy the mezzadri were the luckier ones. Subordinate to them and much more vulnerable economically were the agricultural labourers (braccianti) without land of their own and without a contract of mezzadria; then shepherds, who lived a nomadic life shifting between pastures and markets from season to season.

In the rural hierarchy the mezzadri were the luckier ones. Subordinate to them and much more vulnerable economically were the agricultural labourers (braccianti) without land of their own and without a contract of mezzadria; then shepherds, who lived a nomadic life shifting between pastures and markets from season to season.

The

farmhouse and its outlying buildings, specially from the 18th century,

were designed to guarantee efficiency and self-sufficiency for the peasant family and

for the owner. So these famous terraced hills,

the rows of plantings, the wheat fields, the cypresses and woods, the

fruit trees and mulberries (for silk) were the result of centuries of

collaboration between the landed gentry, who gradually established mixed

farms, and the peasants who gave their lives and labour to the task.

The summer work of crop cultivation was complemented by the winter work of maintenance: building walls, weaving, basketry and other crafts. Techniques did not change drastically for hundreds of years until the 20th century, when the steam-driven thresher was introduced, followed by the haycutter in the 1930s.

More

recently the mezzadria contract included a list and economic assessment

of the most important equipment such as the wagon, the plough, the

haycutter, the supplies of manure given to the farmer ('dead stock') and

the list of the livestock. The most significant element in the yearly

balance of accounts were the all-important oxen, the pride of the farm. The farm

accounts book, presented once a year to the owner (or more probably, his

manager), was the symbol of their relationship, a source of humiliation

and anxiety if debts had been accrued.

The

peasant was expected to improve the property and was encouraged to produce more to sell. And, if things went really well, to feed and clothe his

family better. Little wonder that, on the whole, a mezzadro peasant's life was, with Hobbes, "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short".

In the 1950s approximately 30% of the population of Italy was involved in agriculture. The system of mezzadria was abolished in the 1960s as part of post-war agricultural reform, but since the war farmers had been drifting away from the land to the city for more regulated, better paid jobs and a more comfortable, secure life.

In the 1950s approximately 30% of the population of Italy was involved in agriculture. The system of mezzadria was abolished in the 1960s as part of post-war agricultural reform, but since the war farmers had been drifting away from the land to the city for more regulated, better paid jobs and a more comfortable, secure life.

Thank you for such an informative post! I learned a lot, and especially enjoyed the wonderful contract from 1405 and all the photographs and especially the miniature of the sharecroppers reporting to the farm manager.

ReplyDeleteIt sounds as if much depended on how exploitative the owner of the land was. I wonder, though, whether overall the peasant's life was as "solitary" and "nasty" as that of the people in Hobbes's state of nature. It was certainly safer. But wasn't there also a whole peasant culture of traditions and festivals to brighten the special days of the years?

Without wishing to romanticize premodern rural life, I wonder whether the living conditions of many of these people really improved when they first moved to the cities. Working in factories, housed in cramped quarters, no longer living according to the seasons, nor eating the fresh produce of the land, and no longer enjoying the rich support network of a countryside in which everyone knew one another: the transition surely had its losses as well as its gains.

I am a member and past Secretary of the Toscana Social Club in Melbourne Australia.

ReplyDeleteI have been writing a review on the books of Kinta Beevoir and Iris Origo. Their stories have greatly interested me and I have looked through the internet for information on mezzadria and sharecropping . Came across your blog. Have read it and LOVED IT. My parents lived in Tuscany near Aulla. We migrated to Australia in 1954. I remember my nonno who was a small landowner but we did not have mezzadri and only used our neighbours when needed What you have written about is very much on the mark and whilst I was only 7 when we left I remember fondly the simple happy life we led. It must be remembered that EVERY situation was different there were some very generous "padroni" and some were selfish demanding an cruel. My dad came in 1951 we followed in 1954 for what has been a better life

I shal continue to read your blogs -Congratulations they make me happy

Marisa Bonotto

My family lived this system in Tuscany for centuries. In 1999 I took my mother home to Italy and we lived in the ancestral home and talked to our massive family there about the family's history including the mezzadria, the sharecropper system, and its effects on us. Read my book The Overseer's Family for more about this topic. I am currently trying to compare it to the coal patches created in swpennsylvania from the 1880s.

ReplyDelete