|

| 'The famous river bathes the small plain..' a homage to Pieve Santo Stefano and its river by the poet Carducci |

The archive now holds 7,000 diaries.

Each year the archive selects one hundred amongst the many, which are read and whittled down, by a board of local enthusiasts, to a short-list of eight from which a jury of writers and journalists chooses a winner for the annual Premio Pieve, Pieve Prize.

|

| just some of the diaries preserved by the archive |

But the archive does much more: it has become a resource for students and scholars interested in social history; published many of the diaries as single books (eg; the prize-winning book is always published); prompted the birth of similar institutions in other countries; and furnished material for writers and film makers, notably Nanni Moretti and his I Diari della Sacher, The Sacher Diaries (2001), based on some of the archive's works, extract here.

An interesting off-shoot of the archive is a tiny museum called the Piccolo Museo del Diario where a selection of these diaries is on display. The museum is housed in the former town hall and its offices, one of few buildings in Pieve Santo Stefano to survive the Second World War.

This museum was our goal on a sunny September morning. Pieve Santo Stefano is a small town with ancient Roman origins, like so many in this country. It sits on the river Tiber near to the river's source which symbolically links four regions of central Italy: it is located in Tuscany, but near the borders with Umbria, the Marches and Romagna.

The location is attractive, the town hall impressive for its Andrea della Robbia and the faded frescoes and crests on its walls. A small office is lined with just some of the 7000 diaries - and counting - belonging to the archive. The rest are kept in an apartment which the city council gave to the foundation.

The museum consists of four rooms designed by a Milanese architect which impress for their technological sophistication and flair. A wall in each of the first two rooms is covered with drawers and cupboards, some of which, when opened, reveal either the actual diaries, under glass, displaying an interesting page, or a digital, animated presentation of various pages which can be examined individually through touch- screen technology.

For visitors who do not understand Italian, good English translations are provided in the exhibition although the diaries themselves are not translated.

Voice-overs of actors reading a selection of pages (in Italian) make the experience accessible to the casual visitor, the young or the blind - or the illiterate, I suppose.

Literacy is an interesting aspect of the archive, for two of the most famous diaries in the museum were written by semi-literate people and form the heart of the museum.

The story of each of these ordinary people has become legend.

Vincenzo Rabito was born in Chiaramonte Gulfi, Sicily in 1899: a farm labourer as a child, he soldiered in World War I, went to Africa and survived World War II. He worked as a miner in Germany then returned to Sicily where he married and had three children. He died in 1981.

In 1968, fed up with his life of poverty and an unhappy marriage, he shut himself up in his room and for seven years, despite being semi-literate, set down his life story on an old Olivetti typewriter, letter by letter, punctuating each word with a semi-colon.

The biography, 1,027 pages long, sat in a drawer until 1999 when Rabito's son sent it to the archive where it is now conserved and available for consultation. It won the Premio Pieve in 2000. It is probably the most remarkable autobiography of its type in Italy, both for its story of survival across a century of woes and for the tenacity of the author who barely writes in Italian.

The other extra-ordinary diary is the result of the astonishing labour of a woman from Poggio Rusco, near Mantua in Lombardy. Upon her husband's sudden death in a road accident Clelia Marchi, (1912-2006), contadina, farmer, decided to record the story of her life.

In 1986 at the age of 74 she arrived at Pieve Santo Stefano with a bedsheet under her arm. She had come by train and bus all the way from Mantua. Her autobiography was written on her linen bedsheet.

Care persone fatene tesoro di questo lenzuolo

che c’è un pò della vita mia; è mio marito;

Clelia Marchi (72) anni hà scritto

la storia della gente della sua terra,

riempendo un lenzuolo di scritte,

dai lavori agricoli, agli affetti.

"Dear people, treasure this sheet, where there is something of my life; it is my husband; Clelia Marchi (72) years old has written the story of her people and her land, filling a sheet with writings about things from farm work to feelings."

These are the opening lines of her story.

When Clelia, who had always recorded poetry and thoughts, decided to write her autobiography, she remembered how her schoolteacher had said that the Etruscans used to wrap their mummies in sheets. "I cannot use the sheets with my husband and so I thought to use them to write."

It was a way of commemorating her life and her husband, whom she had known since she was fourteen and loved since she was sixteen.

The archive has an excellent, informative site in Italian with a page dedicated to the museum

Many diary extracts are also available online.

The Piccolo Museo del Diario in Piazza Pellegrini 1, Pieve Santo Stefano,is open to the public Monday to Friday from 9 to 13 and from 1530 to 18 as well as Saturday and Sunday between 15 and 18.

For a visit please ask at the Archive in Piazza Fanfani, 14 and a guide will accompany you to the museum.

Entry for now is free but visitors are warmly encouraged to buy the publications or make a donation.

The location is attractive, the town hall impressive for its Andrea della Robbia and the faded frescoes and crests on its walls. A small office is lined with just some of the 7000 diaries - and counting - belonging to the archive. The rest are kept in an apartment which the city council gave to the foundation.

The museum consists of four rooms designed by a Milanese architect which impress for their technological sophistication and flair. A wall in each of the first two rooms is covered with drawers and cupboards, some of which, when opened, reveal either the actual diaries, under glass, displaying an interesting page, or a digital, animated presentation of various pages which can be examined individually through touch- screen technology.

|

| the light show is perhaps supposed to emphasise that we have been given access to people's otherwise private lives |

|

| Saverio Tutino, the creator and founder of the archive, remembered here in a reconstruction of his desk and in some pages of his own minute and orderly diary |

|

| These are the love letters of a Countess from the 19th century who covered her pages in both directions: to thwart prying eyes or to save paper? We shall never know. |

|

| the archive contains many war diaries and letters |

|

| some diaries are illustrated, like this one from the 1980s |

|

| letters from the Front: postcards and letters recounting the fears of a young soldier caught up in the horrors of the Great War |

Literacy is an interesting aspect of the archive, for two of the most famous diaries in the museum were written by semi-literate people and form the heart of the museum.

The story of each of these ordinary people has become legend.

Vincenzo Rabito was born in Chiaramonte Gulfi, Sicily in 1899: a farm labourer as a child, he soldiered in World War I, went to Africa and survived World War II. He worked as a miner in Germany then returned to Sicily where he married and had three children. He died in 1981.

|

| multimedia exhibit of the opening of Vincenzo Rabito's autobiography: the typewriter displayed is identical to the one on which he painfully tapped out his story |

The biography, 1,027 pages long, sat in a drawer until 1999 when Rabito's son sent it to the archive where it is now conserved and available for consultation. It won the Premio Pieve in 2000. It is probably the most remarkable autobiography of its type in Italy, both for its story of survival across a century of woes and for the tenacity of the author who barely writes in Italian.

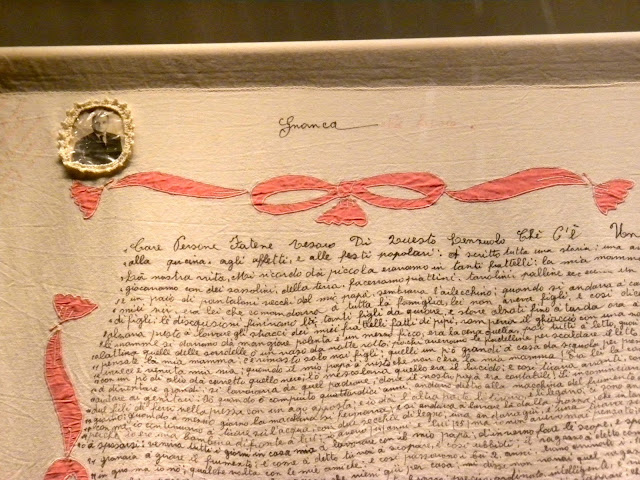

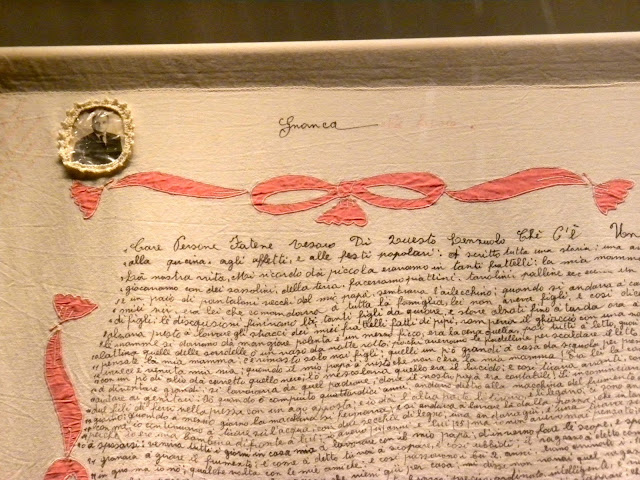

The other extra-ordinary diary is the result of the astonishing labour of a woman from Poggio Rusco, near Mantua in Lombardy. Upon her husband's sudden death in a road accident Clelia Marchi, (1912-2006), contadina, farmer, decided to record the story of her life.

In 1986 at the age of 74 she arrived at Pieve Santo Stefano with a bedsheet under her arm. She had come by train and bus all the way from Mantua. Her autobiography was written on her linen bedsheet.

Care persone fatene tesoro di questo lenzuolo

che c’è un pò della vita mia; è mio marito;

Clelia Marchi (72) anni hà scritto

la storia della gente della sua terra,

riempendo un lenzuolo di scritte,

dai lavori agricoli, agli affetti.

"Dear people, treasure this sheet, where there is something of my life; it is my husband; Clelia Marchi (72) years old has written the story of her people and her land, filling a sheet with writings about things from farm work to feelings."

These are the opening lines of her story.

When Clelia, who had always recorded poetry and thoughts, decided to write her autobiography, she remembered how her schoolteacher had said that the Etruscans used to wrap their mummies in sheets. "I cannot use the sheets with my husband and so I thought to use them to write."

It was a way of commemorating her life and her husband, whom she had known since she was fourteen and loved since she was sixteen.

|

| Just a few of the archive's many publications, including the DVD of Nanni Moretti's film with its diary excerpts recounted by the diarists themselves |

The archive has an excellent, informative site in Italian with a page dedicated to the museum

Many diary extracts are also available online.

The Piccolo Museo del Diario in Piazza Pellegrini 1, Pieve Santo Stefano,is open to the public Monday to Friday from 9 to 13 and from 1530 to 18 as well as Saturday and Sunday between 15 and 18.

For a visit please ask at the Archive in Piazza Fanfani, 14 and a guide will accompany you to the museum.

Entry for now is free but visitors are warmly encouraged to buy the publications or make a donation.

Such a touching, useful Museo di Diario. The story of the widow and her story so painstakingly written and decorated on her linen sheets is beautiful, one of many remarkable little social but important histories.

ReplyDelete